Editor’s Note: Sarah Hawley is an associate professor in the Division of General Medicine at the University of Michigan and a research investigator at the Ann Arbor VA Center of Excellence in Clinical Management Research. Her primary research is in decision making related to cancer prevention and control.

Story highlights

Sarah Hawley: Jolie, who's high risk, a good candidate for mastectomy, but word of caution

She says women with cancer in one breast increasingly having other breast removed too

She says risk of cancer in healthy breast is less than 1%; overtreatment a concern

Hawley: Women need control over health decisions, but must have accurate info on choices

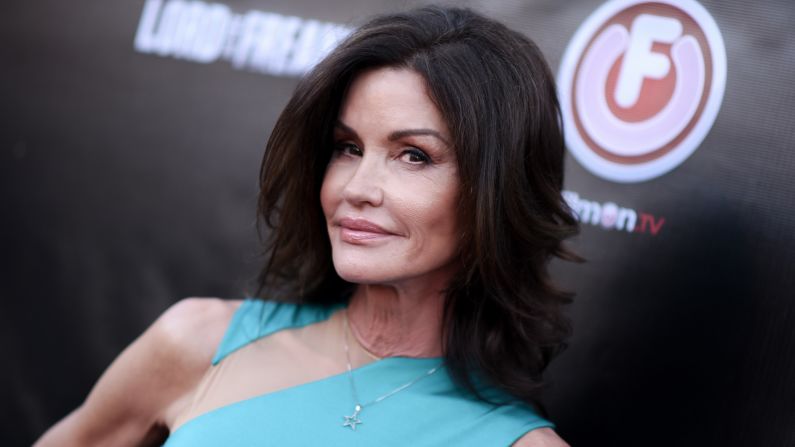

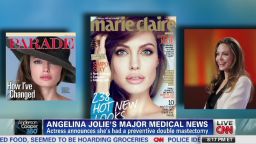

Angeline Jolie, who has stated that she is a carrier of the gene mutation BRCA1, appears to have been a good candidate for the bilateral prophylactic mastectomy she underwent recently to remove both of her breasts. In Jolie’s case – as with others who have openly discussed a similar action, such as Miss American contestant Allyn Rose and celebrity Sharon Osbourne – the decision is appropriate: Having a genetic mutation, as these women do, puts a woman at very high risk for developing breast cancer in her lifetime.

But it possible that these very public decisions could lead more women with cancer diagnosed in one breast to consider having their second, nonaffected breast removed. This is called contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and it is on the rise in the U.S. Data from large cancer registry studies, for one example, have shown that the overall rate of CPM among women with stage I, II or III breast cancer significantly increased from 1.8% in 1998 to 4.5% in 2003. Looking only at patients treated with mastectomy, the CPM rate grew from 4.2% in 1998 to 11.0% in 2003.

It is important, on the news of Jolie’s decision, to caution women that CPM should be done only for the same reason as bilateral prophylactic mastectomies – the presence of BRCA1 OF BRCA2. While many women who choose CPM do carry one of these genes, our research suggests that most do not.

Considered in the context of history, this is a jarring development. Back in the 1970s, women with breast cancer and their supporters pushed to have the option of breast conserving surgery (BCS or “lumpectomy”) made available as an option to treat breast cancer.

They argued then that they should have access to a less invasive option than mastectomy (surgery to remove all breast tissue), particularly when randomized trials suggested the two treatments gave women the same chance of long-term survival. Yet in the United States we now find ourselves on the opposite end of the spectrum, with patients largely driving decisions – electing to undergo this most extensive treatment option for breast cancer.

It would be almost unheard of for a woman without cancer to have a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, as Jolie did, unless she had a genetic mutation.

So why would a woman who has cancer in one breast choose to have a second, healthy breast removed? Our research suggests that patients are worried about recurrence. But for the average breast cancer patient who has neither the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation nor a close relative with breast cancer (Jolie’s mother, for example, died from ovarian cancer), the risk of a new breast cancer in the nonaffected breast is less than 1%.

Having the nonaffected breast removed will not translate into any additional survival benefit beyond what is conferred by treating the existing cancer. In fact, research has shown that many women who choose CPM could have been treated with only a lumpectomy, plus radiotherapy, in the affected breast.

Given the extent of the procedure, that CPM is done on patients without clinical reason raises strong concerns about overtreatment. This is perhaps the only example of removing a nonaffected organ based on what appears to be patient misunderstanding of the potential benefit of the surgery.

It’s unlikely that a surgeon would agree to remove the entire colon of a patient with resectable colon cancer because the patient was worried about getting more colon cancer. Similarly, it is difficult to imagine a man with testicular cancer requesting to have both the affected and nonaffected testicles removed.

In this era of patient-centered care, women do need to feel empowered to make the choices that are best for them in treating their breast cancer. Yet because these choices are so difficult, it is imperative that they be based on accurate understanding of the risks and benefits of treatment. Perhaps we need to turn our attention to helping women remember why they advocated for less invasive options nearly 40 years ago.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Sarah Hawley.